Scroll to:

Impact of tin ore mining on the streamflow of small rivers in mining regions

https://doi.org/10.17073/2500-0632-2025-04-392

Abstract

Mineral extraction exerts a significant impact on the environment, particularly on the hydrological regime of rivers. The placement of tailings storage facilities in river valleys is a common practice in ore processing. Forest stands and river networks in such areas undergo intensive transformation involving large-scale deforestation with removal of the root-inhabited soil layer and alteration of river channels. As a result, the streamflow in the affected sections becomes less abundant. Since the 1970s, active tin ore mining and processing have been carried out in the Silinka River basin of the Khabarovsk Territory. Mining activities have produced technogenic landforms such as tailings storage facilities, open pits, and waste dumps, which pose both ecological and technogenic hazards and act as sources of pollution for groundwater, surface water, soil, vegetation, and the atmosphere. Forest cover is one of the key indicators determining river runoff and can be used to estimate the capitalized value of 1 km2 of the study area. Using the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), this study assessed the impact of tin ore mining on the Silinka River basin. The results indicate a 25% decrease in the average capitalized value of 1 km2 of the study area.

Keywords

For citations:

Rastanina N.K., Golubev D.A., Kayumov N.A., Rastanin P.L., Popadyev I.A. Impact of tin ore mining on the streamflow of small rivers in mining regions. Mining Science and Technology (Russia). 2025;10(4):369–378. https://doi.org/10.17073/2500-0632-2025-04-392

Impact of tin ore mining on the streamflow of small rivers in mining regions

Introduction

Mineral extraction is one of the key sources of revenue for the Russian Federation but also results in significant negative environmental impacts. More than 80 billion tons of mining waste have already accumulated in Russia, occupying a total area of 1.1 million hectares disturbed by mining activities. Each year, this number continues to increase, leading to the degradation of essential forest functions in areas located at or near mining and mineral processing sites. The establishment of such facilities is accompanied by extensive deforestation, removal of the fertile soil layer, and alterations to river channels and runoff patterns1 [1].

The condition of forest ecosystems plays a crucial role in the formation of river basins through surface runoff, particularly in mining regions [2]. M. E. Tkachenko (1952) considered the water protection role of forests in a broader context, not limiting it to the quantitative assessment of runoff. In his view, the beneficial effects of forests extend not only to surface waters (rivers, lakes, reservoirs) but also to groundwater, which often serves as the main source of water supply for both communities and industrial enterprises [3].

According to the concept of the general moisture-retaining function of forests, these ecosystems contribute to moisture accumulation within catchment areas, thereby increasing the total annual runoff [4]. However, an opposing view exists that considers forests as strong evaporators of moisture, suggesting that an increase in forest cover reduces river runoff [5]. O. I. Krestovsky, based on studies in the southern taiga, established that after clear cutting, the evaporation component decreases by 20–40%. As a result, the runoff regime deteriorates: during the high-water period, liquid runoff increases, whereas during low-water periods, rivers become shallower [6]. Anthropogenic impacts not only modify the conditions of various runoff types [7–9] but also transform the characteristics of diffuse pollution, affecting the quality of surface water bodies [10]. This is particularly significant when toxic elements such as heavy metals and arsenic are present, leading to suppression and die-off of forest vegetation due to their spread across natural and technogenic environmental components [11].

Thus, the formation of river runoff may depend on the following factors:

- Natural and climatic conditions, which influence the total annual river runoff and its distribution through the amount and type of precipitation, its spatial and temporal distribution, air temperature and humidity, and wind speed, all of which determine runoff losses due to evaporation [4, 12];

- Topography, including the steepness of slopes and channel gradients, which shape the conditions for infiltration of melt and rainwater into the soil, slope and subsurface flow, and recharge of groundwater horizons [13];

- Soil and hydrological conditions, where higher rock permeability and thicker deposits provide greater underground storage capacity and regulatory ability, ensuring more stable runoff throughout the year [14];

- Vegetation cover, which affects the rate of snowmelt and surface water flow, thereby influencing the overall hydrological regime [13];

- Catchment size and shape, which correlate directly with the uniformity of runoff through variations in the share of subsurface (groundwater) recharge [15];

- Lake and wetland coverage within the catchment, which tends to reduce river runoff because highly saturated lake–bog systems or lowland wetlands regulate flow and decrease the amplitude of discharge fluctuations [16];

- Anthropogenic influences, including regulation and redistribution of river flow, water abstraction and discharge in industry and agriculture, land reclamation, and other activities that fundamentally alter the natural runoff regime [17];

- Forest cover, which is one of the key factors regulating the water balance, as forest stands promote infiltration and maintain base flow. Deforestation reduces moisture retention, thereby amplifying seasonal fluctuations in river discharge [18];

- Soil disturbance, particularly the removal of the root-inhabited layer, which decreases the soil’s water-retaining capacity [19];

- Mining facilities, such as tailings storage facilities and waste rock dumps, which modify the filtration properties of catchments, while pollutants can alter the chemical composition of water [20, 21].

The tailings storage facilities of the Solnechny Mining and Processing Plant (Solnechny MPP) represent sites of ecological and technogenic hazard, acting as sources of contamination for groundwater, surface water, soils, vegetation, and the atmosphere due to dust emissions from their surfaces [14, 22, 23]. The purpose of this study is to assess the impact of mining operations on river runoff formation and the reduction of streamflow in small rivers within the Silinka River basin. The study addressed the following objectives: 1 – to analyze literature data on factors affecting the formation of river runoff in small rivers; 2 – to describe the disturbed area occupied by the tin mining enterprise; 3 – to assess the forest cover and water-protective function of forests within the influence zone of the Solnechny Mining and Processing Plant.

1 State (National) Report on the Status and Use of Lands.URL: https://rosreestr.gov.ru/activity/gosudarstvennoe-upravlenie-v-sfere-ispolzovaniya-i-okhrany-zemel/gosudarstvennyy-natsionalnyy-doklad-o-sostoyanii-i-ispolzovanii-zemel-rossiyskoy-federatsii (Accessed: 7 November 2024).

Study area and methods

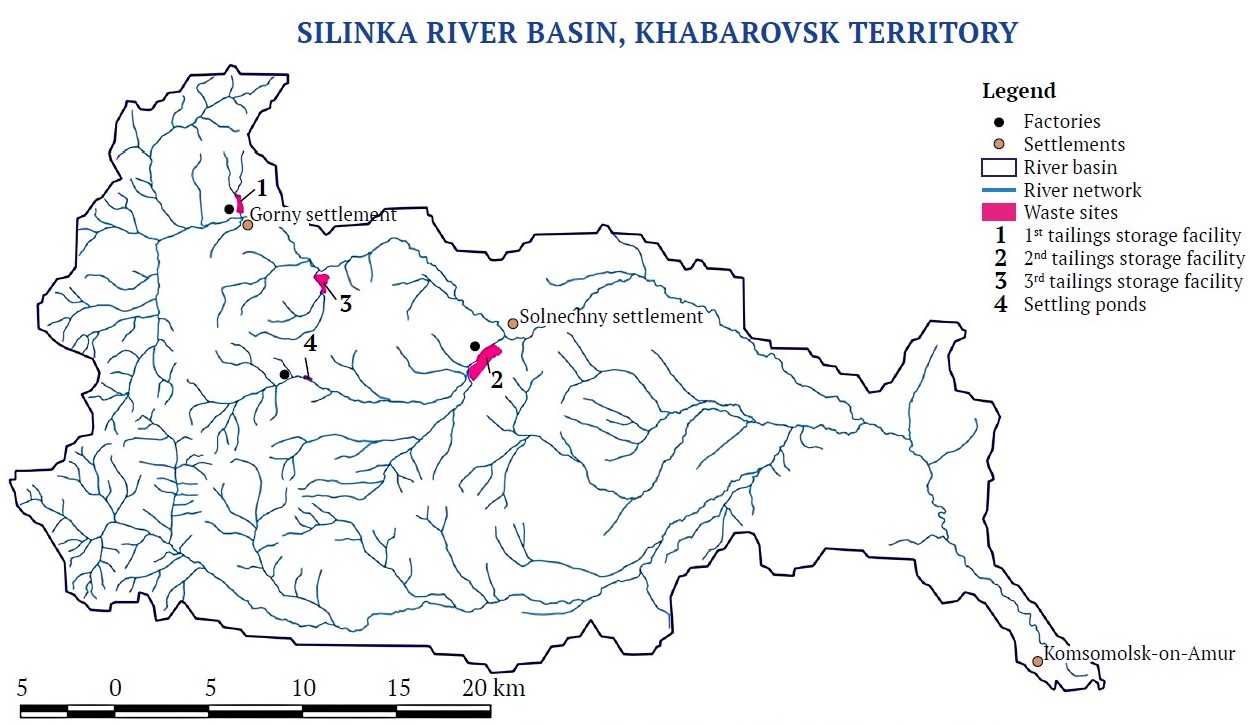

The study area comprises the disturbed lands of the former Solnechny MPP, located within the Silinka River catchment, Solnechny District, Khabarovsk Territory [13, 24]. Solnechny MPP was the district’s principal enterprise and the main economic driver of the area. Since 1969, large volumes of toxic waste have accumulated and been stored in three tailings storage facilities (TSFs).

As a result of open-pit and underground mining of cassiterite and cassiterite–sulfide deposits, large open pits and dumps of substandard ores and host rocks remain on the surface, along with numerous adits from which waste rock and mine water are discharged onto the slopes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Schematic map of technogenic facilities within the Silinka River basin

The mining–technogenic system that developed in the Komsomolsk tin-ore district has intensified supergene processes due to the expanded contact area between weathering agents and exposed surfaces of sulfide ores, as well as finely ground sulfides in the tailings. These processes have progressed to a more advanced technogenic stage.

The tailings storage facilities of the Solnechny MPP are composed of gray hydraulic-fill sands, sometimes stained brownish by iron hydroxides formed through oxidation of sulfides. The grain size of the sands is predominantly less than 0.5 mm. Coarse fractions greater than 2 mm account for about 1% of the total volume (up to 3% in certain layers), while 70–83% of the material consists of particles in the 0.1–0.5 mm range, and 13–14% are finer than 0.1 mm (up to 28% in individual horizons). The vertical grain-size distribution is heterogeneous. According to previous assessments of waste hazard classes, the dried tailings belong to the highly hazardous toxicity class [25]. No land reclamation was undertaken in the disturbed area, despite the requirements of the Russian Federation’s Law on Subsoil [26].

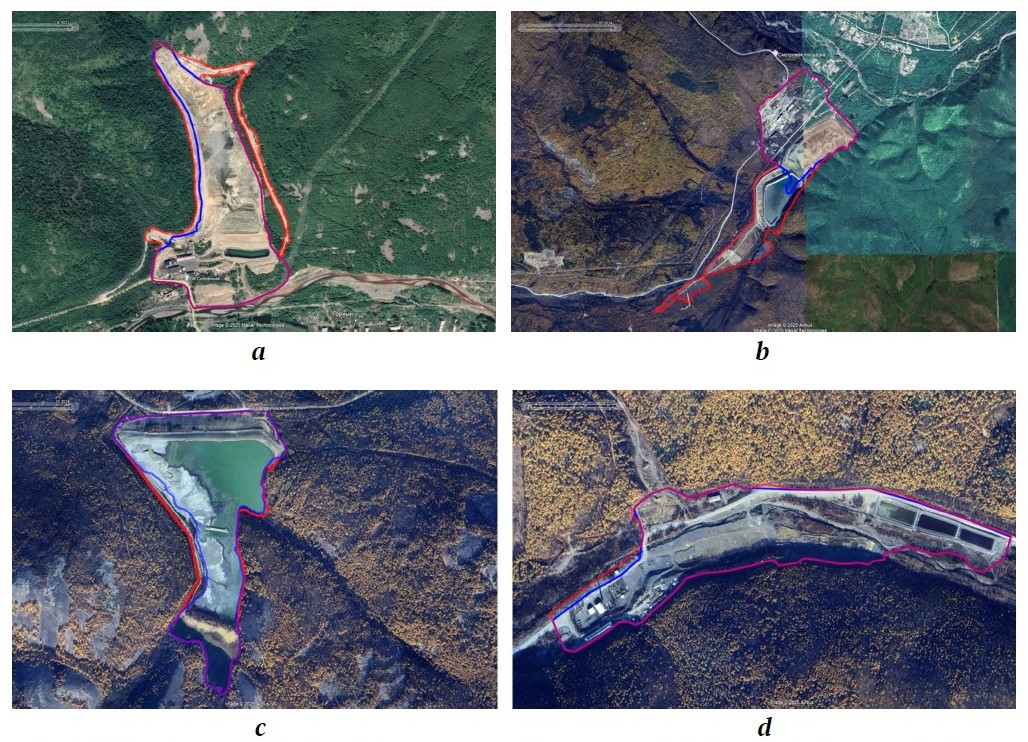

The first tailings storage facility lies opposite the settlement of Gorny, approximately 100–500 m from the concentration plant. Its area is 44 hectares, with a total volume of 10.4 million tons (Fig. 2, a).

Fig. 2. Mining-disturbed areas of the former Solnechny Mining and Processing Plant:

a – operating processing plant of JSC Tin Ore Company; b – surface of the second tailings storage facility; c – surface of the third tailings storage facility; d – surface of the settling pond at the Festivalnoye deposit

The waste material from the second tailings storage facility is currently being reprocessed by LLC Geoprominvest to produce tin and copper concentrates (Fig. 2, b).

At present, the assets of the former Solnechny MPP, including the Festivalnoye and Perevalnoye deposits, are managed by JSC Tin Ore Company, which has restarted tin and tungsten mining operations and continues to fill the third tailings storage facility (Fig. 2 c, d).

The forest cover of the Silinka River basin was assessed using the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) calculated from Landsat 8 satellite data processed in QGIS. According to previous research [27], NDVI values below 0.3 correspond to non-forested areas, while values above 0.3 indicate forested land.

The ecological and economic assessment of the impact of mineral exploration and mining activities is not standardized and lacks a unified methodological framework. In this study, cartographic modeling was performed using the open-source software QGIS 3.10, along with the recommended method for estimating the economic damage to river runoff based on forest cover [28]:

M = −1.02 + 0.068 × F, (1)

where M is the runoff modulus per 1 km2 of the catchment area, and F is the forest cover percentage.

Results and discussion

The catchment area of the Silinka River is 1,016 km2 [29]. The river basin belongs to the Far Eastern taiga forest region and lies within the boundaries of two forestry districts – Komsomolsk and Solnechny. In the northwest, it borders the protected area of the regional natural monument “Amut Landslide Lake,” while the rest of the forested land is located within the green zone or classified as production forests.

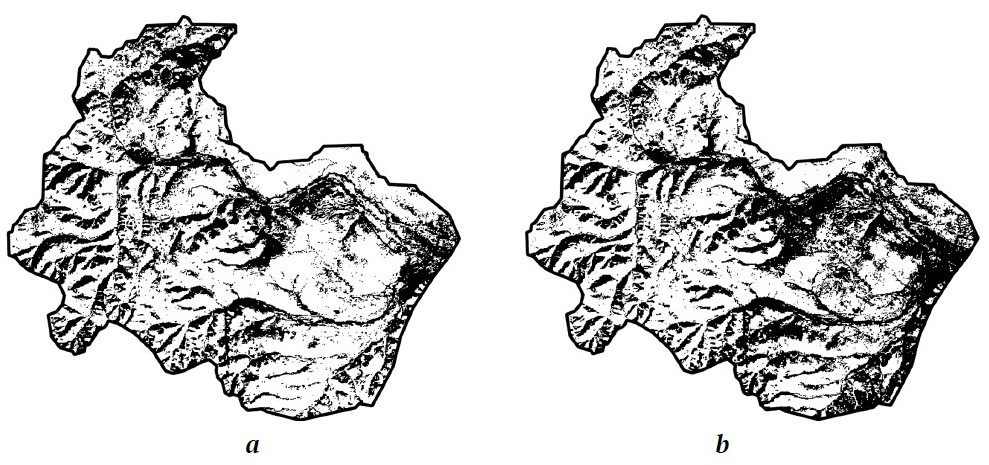

Between 2012 and 2024, the total area of mining-disturbed lands within the Silinka River basin increased from 341.5 ha to 430.8 ha (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Schematic map of mining-disturbed areas: a – first tailings storage facility;

b – second tailings storage facility; c – third tailings storage facility; d – settling pond at the Festivalnoye deposit.

Note: blue – extent of the disturbed area in 2012; red – extent of the disturbed areas in 2024; purple – combined outline for 2012 and 2024.

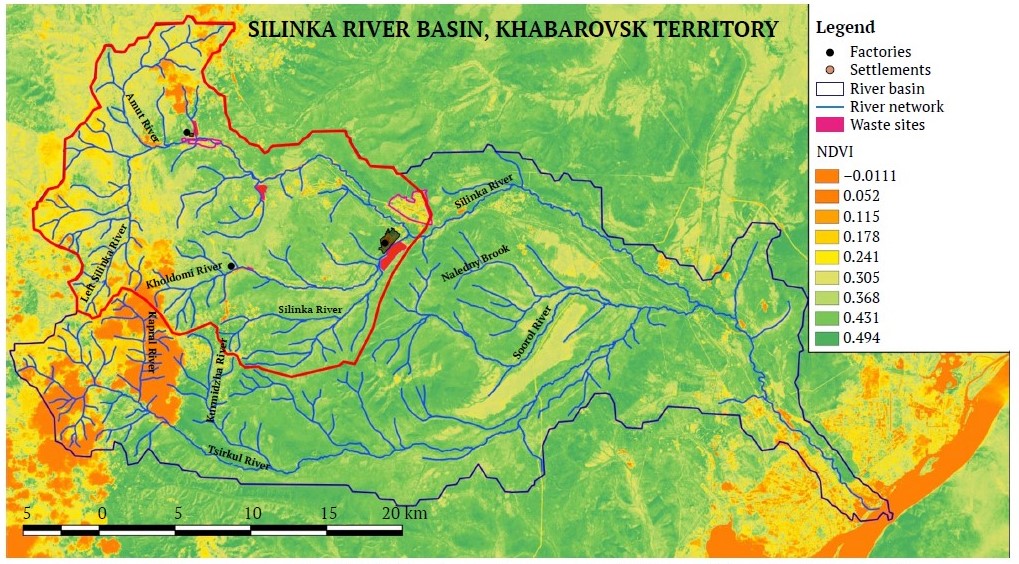

According to GIS-based analysis using the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) calculated in QGIS from Landsat satellite data, the maximum NDVI value in the Silinka River basin does not exceed 0.494, which corresponds to a moderate level of forest biomass development (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Schematic map of the Silinka River basin with Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI).

Note: boundary of the analysed river network section

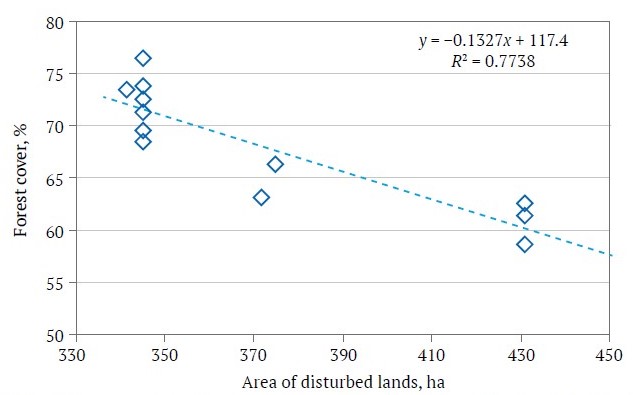

Analysis of the resulting raster images (Table 1, Fig. 5) showed that forest cover in the Silinka River basin within the areas affected by the Solnechny MPP has changed in response to the expansion of mining-disturbed land (Fig. 6). NDVI-based estimation of forest cover indicated a decrease of 14.8%.

Table 1

Forest cover parameters derived from NDVI for river basins hosting technogenic facilities of the studied mining enterprises

Year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

Forest cover,% | 73.5 | 69.6 | 73.8 | 68.5 | 76.5 | 71.3 | 72.6 | 63.2 | 66.3 | 58.7 | 62.6 | 61.4 |

Area of the 1st tailings storage facility, ha | 40.5 | 40.5 | 40.5 | 40.5 | 40.5 | 40.5 | 40.5 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 |

Area of the 2nd tailings storage facility, ha | 195 | 195 | 233 | 233 | 233 | 233 | 233 | 256 | 256 | 312 | 312 | 312 |

Area of the 3rd tailings storage facility, ha | 40.1 | 40.1 | 40.8 | 40.8 | 40.8 | 40.9 | 40.9 | 40.9 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 |

Area of the settling pond, ha | 30.8 | 30.8 | 30.8 | 30.8 | 30.8 | 30.8 | 30.8 | 30.8 | 30.8 | 30.8 | 30.8 | 30.8 |

Fig. 5. NDVI-based forest cover in river basins hosting mining facilities, 2012 (a) and 2024 (b)

Note: black pixels represent non-forested areas

Fig. 6. Relationship between forest cover and the extent of disturbed land in the Silinka River basin

Based on the recommendations for estimating economic losses associated with changes in river runoff as a function of forest cover (Eq. 1), the specific runoff from 1 km2 of the catchment area was 3.978 × 103 m3 in 2012 and decreased to 2.9726 × 103 m3 by 2024.

The statutory charge for withdrawing 103 m3 of surface water from water bodies within the Amur River basin (Far Eastern region) within the approved quarterly abstraction limits is 264 rubles. For withdrawals exceeding these limits, the rate is applied at five times the standard level. In addition, a coefficient of 1.1 is applied to the water-use tax rate in 2024.

As a result, the charge for 103 m3 of water in 2012 and 2024 amounted to 5,776.05 rubles and 4,314.76 rubles, respectively.

The capitalized value of the study2 area amounted to 57,760.5 rubles in 2012 and 43,147.6 rubles in 2024.

The reduction in the value of 1 km2 of territory performing water-protection functions within the Silinka River basin can therefore be expressed as the difference between the capitalized values calculated for 2012 and 2024.

According to the calculations, the average value per 1 km2 of the study area decreased by 14,612.9 rubles, which corresponds to a reduction of about 25% as a result of mining activity.

2 Order No. 81 of February 11, 1998 "On Approval of the Methodology for Calculating the Damage from Groundwater Pollution". State Committee of the Russian Federation for Environmental Protection. 1998.

Conclusion

Geoinformation analysis based on the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) revealed a 14.8% decrease in forest cover within the section of the Silinka River basin affected by the former Solnechny Mining and Processing Plant, relative to the 2012 baseline. This confirms the degradation of the water-regulating function of the vegetation cover. The reduction in forest cover is accompanied by a decrease in specific runoff of 1.0064 × 103 m3 per km2, which is equivalent to a 25% decline in streamflow.

The calculated average value per 1 km2 of the study area in 2024 decreased by 14,612.9 rubles due to mining operations. Thus, the extraction of tin ore within the Silinka River basin (Solnechny District, Khabarovsk Territory) leads to a reduction in forest cover, which in turn causes a directly proportional decrease in the streamflow of small rivers.

References

1. Boltryov V. B., Degtyarev S. A., Seleznev S. G., Storozhenko, L. A. Ecological damages in territories of mining waste formation and accumulation. In: Osipov V. I., Maksimovich N. G., Baryakh A. A., et al. (Eds.), Sergeevskie Chteniya: Proceedings of the Annual Session of the RAS Scientific Council on Geoecology, Engineering Geology, and Hydrogeology. April 2–4, 2019. Perm: State National Research University. Vol. 21. Pp. 151–156. (In Russ.)

2. Rybnikova L. S. Technogenic impact of the Urals mining works upon the hydrosphere status. Water Sector of Russia: Problems, Technologies, Management. 2012;(1):74–91. (In Russ.)

3. Tkachenko M. E. General forestry. 2nd ed. Moscow: Goslesbumizdat; 1952. 598 p. (In Russ.)

4. Pobedinskiy A. V. Water protection and soil conservation role of forests. 2nd ed. Pushkino: VNIILM; 2013. 208 p. (In Russ.)

5. Kasimov D. V., Kasimov V. D. Some approaches to assessing ecosystem functions of forest stands in environmental management practice. Moscow: Mir Nauki; 2015. 91 p. (In Russ.)

6. Gaparov K. K. The influence of forestry practices on hydrological and protective functions of spruce forests in Issyk-Kul region. Bishkek: Institute of Forest and Nut Farming named after Prof. P. A. Gan of the National Academy of Sciences of the Kyrgyz Republic; 2007. 103 p. (In Russ.)

7. Krestovskiy O. I. The influence of forest cutting and restoration on river water content. Saint Petersburg: Gidrometeoizdat; 1986. 118 p. (In Russ.)

8. Alekseevskiy N. I. River runoff: geographical role and indicative properties. Problems of Geography. 2012;133:48–71. (In Russ.)

9. Koronkevich N. I., Melnik K. S. Impact of urbanized landscapes on the river flow in Europe. Izvestiya Rossiiskoi Akademii Nauk. Seriya Geograficheskaya. 2019;(3):78–87. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.31857/S2587-55662019378-87

10. Yasinskiy S. V., Venitsianov E. V., Vishnevskaya I. A. Diffuse pollution of waterbodies and assessment of nutrient removal under different land-use scenarios in a catchment area. Vodnye Resursy. 2019;46(2):232–244. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.31857/S0321-0596462232-244

11. Buzmakov S. A., Nazarov A. V., Sannikov P. Yu. Influence of mining on vegetation. Izvestia of Samara Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences. 2012;(5):261–263. (In Russ.)

12. Lebedev Yu. V., Neklyudov I. A. Assessment of water conservation and water regulation functions of forests: methodological guidelines. Yekaterinburg: Ural State Forest Engineering University; 2012. 36 p. (In Russ.)

13. Kireeva M. B., Ilich V. P., Sazonov A. A., Mikhaylyukova P. G. An assessment of changes in land usage and their impact on Don River basin runoff using satellite imagery. Sovremennye Problemy Distantsionnogo Zondirovaniya Zemli iz Kosmosa. 2018;15(2):191–200. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.21046/2070-7401-2018-15-2-191-200

14. Makarov V. N. Geochemical assessment of tailings of mining and processing plants in Yakutia. Nedropolzovanie XXI Vek. 2023;(3–4):34–41. (In Russ.)

15. Abakumova V. Y. Research of relief impact on river network structure (Zabaikalsky Krai). In: Environmental cooperation in transboundary ecological regions: Russia – China – Mongolia. Chita: Poisk; 2012. Vol. 3. Pt. 1. Pp. 199–203. (In Russ.)

16. Inishev N. G., Voronova A. A. The influence of landscape features of wetland watersheds on the hydrographs of spring flood. In: Inisheva L. I (Ed.) Swamps and the Biosphere. Proceedings of the IX All-Russian School-Conference of Young Scientists with international participation. Vyatkino, Vladimir Oblast, September 14–18, 2015. Vyatkino: PresSto; 2015. Pp. 199–203. (In Russ.)

17. Georgiadi A. G., Koronkevich N. I., Zaitseva I. S., et al. Climatic and anthropogenic factors in long-term alterations of the Volga river runoff. Water Sector of Russia: Problems, Technologies, Management. 2013;(4):4–19. (In Russ.)

18. Zemlyanukhin I. P., Radcevich G. A. Influence of morphology and woodiness of reservoirs on formation of the drain. Modeli i Tekhnologii Prirodoustroistva (Regional'nyi Aspekt). 2016;(2):41–46. (In Russ.)

19. Konokova B. A. The problem of preservation of fresh water quality in the mountains. New Technologies. 2012;(2):1–6. (In Russ.)

20. Denmukhametov R. R., Sharifullin A. N. Antropogenic components of the river flow dissolved substances. Ekologicheskiy Konsalting. 2011;(1):34–41. (In Russ.)

21. Krupskaya L. T., Melkonyan R. G., Zvereva V. P., et al. Ecological hazard of accumulated mining waste and recommendations on risk reduction in the Far Eastern Federal District. Mining Informational and Analytical Bulletin. 2018;(12):102–112. (In Russ.)

22. Krupskaya L.T., Golubev D. A., Rastanina N. K., Filatova M. Yu. Reclamation of tailings storage surface at a closed mine in the Primorsky Krai by bio remediation. Mining Informational and Analytical Bulletin. 2019;(9):138–148. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.25018/0236-1493-2019-09-0-138-148

23. Nazarkina A. V. Physical properties and hydraulic regime of alluvial soils in floodplains of rivers in the Sikhote-Alin mountains. Eurasian Soil Science. 2008;41(5):509–518. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1064229308050062 (Orig. ver.: Nazarkina A. V. Physical properties and hydraulic regime of alluvial soils in floodplains of rivers in the Sikhote-Alin mountains. Pochvovedenie. 2008;(5):576–586. (In Russ.))

24. Rastanina N. K., Kolobanov K. A. Impact of technogenic dust pollution from the closed mining enterprise in the Amur Region on the ecosphere and human health. Mining Science and Technology (Russia). 2021;6(1):16–22. https://doi.org/10.17073/2500-0632-2021-1-16-22

25. Rastanina N. K., Galanina I. A., Popadyev I. A. Mining and environmental monitoring of soil changes within the boundaries of the influence of tin ore mining in the Amur Region. Modern Science: Actual Problems of Theory & Practice. Series Natural & Technical Sciences. 2024;(5):22–26. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.37882/2223-2966.2024.05.28

26. Krupskaya L.T., Ionkin K. V., Krupskiy A. V., et al. On the issue of assessing tailing dumps as a source of environmental pollution. Mining Informational and Analytical Bulletin. 2009;(5):234–241. (In Russ.)

27. Komarov A.A. Assessment of grass stand condition using NDVI vegetation index. Izvestiya Saint-Petersburg State Agrarian University. 2018;(2):124–129. (In Russ.)

28. Tishkov A. A., Bobylev S. N., Medvedeva O. E., et al. Economics of biodiversity. Moscow: Institut Ekonomiki Prirodopol'zovaniya; 2002. 604 p. (In Russ.)

29. Belov D. V., Brovko P. F. Recreational potential of the Silinka River basin (Khabarovsk region). The Pacific Geography. 2020;(4):65–73. (In Russ.) https://doi.org/10.35735/tig.2020.4.4.007

About the Authors

N. K. RastaninaRussian Federation

Natalia K. Rastanina – Cand. Sci. (Biol.), Associate Professor of the Higher School of Industrial Engineering

Khabarovsk

D. A. Golubev

Russian Federation

Dmitry A. Golubev – Cand. Sci. (Eng.), Associate Professor of the Higher School of Management; Leading Researcher of the Department of Forest Protection and Forest Ecology

Khabarovsk

N. A. Kayumov

Russian Federation

Nikita A. Kayumov – Student

Khabarovsk

P. L. Rastanin

Russian Federation

Pavel L. Rastanin – Student

Khabarovsk

I. A. Popadyev

Russian Federation

Ilya A. Popadyev – Student

Khabarovsk

Review

For citations:

Rastanina N.K., Golubev D.A., Kayumov N.A., Rastanin P.L., Popadyev I.A. Impact of tin ore mining on the streamflow of small rivers in mining regions. Mining Science and Technology (Russia). 2025;10(4):369–378. https://doi.org/10.17073/2500-0632-2025-04-392

JATS XML